Turning Grit Into Gold

- mikestubbsart

- Sep 3, 2023

- 13 min read

Updated: Jan 11

Curatorial Concept by Mike Stubbs

Is reading this text pleasurable, useful, or both. Are you working now?

I hope you value both my physical effort in typing on these computer keys, and also the knowledge and thinking power I am bringing to the page (ChatGPT or other large language learning models have had only a small part in this process). I am not encouraging the machine to take over my job as writer or curator, and I like working as it gives me a chance to process the world, while work gives us a sense of purpose. With automation, that sense may be removed. Until then, we need to turn up to get paid, to trade stuff, and to buy food, etc., or otherwise we need to come from families with wealth. But even that has its problems, because surely a sense of satisfaction or purpose is hard-wired into earning an honest wage. Or is this an outdated concept from the first Industrial Revolution, where state, church, mine or factory owners organised working people and instilled a sense of guilt in those that didn’t or couldn’t work.

Work to rule, the ‘go-slow’, or time-wasting, have traditionally formed types of protest within historical settings of industrial disputes, and usually precede a strike. Increasingly, we see all generations losing a sense of belief in work and its structures, especially following the pandemic; globally, there has been a shift in values and work patterns, demonstrated in such movements dubbed the Lying Flat or the Tang Ping movement. Being seen to move slowly, or to make no physical movement at all, is a clear signal of non-activity or disruptive behaviour.

Historically, the stage before strike action begins, whether swinging a pickaxe or tapping out keystrokes. Slow movement and duration also form the components of performance art or Actionism. Dadaism actively confounded oppressive systems of war and logic. Artists such as Tristan Tzara and Kurt Schwitters were major proponents of these movements, and they created art which challenged rationality and order. Artists have continued to deconstruct or reappropriate, not only through ideological motivations, but also through an ontological approach to the world, reflecting on our assumptions as to how it functions; the curiosity to look at things more closely and to observe subtle differences and values. (On the subject of pay, arts workers in the UK – where I live – earn an average of £2.62/hour.) Artists are neither loafing nor lazing; they are driven, motivated and virtuous – and they create new value for themselves, to share with others. However, this contradiction and tension between risk-taking and the desire to reconsider value can profoundly challenge our naturalised paradigms of efficiency.

In the 1970s, performance artists Chris Burden and Tehching Hsieh committed dangerous acts: Shoot (1971), where Burden is shot in the arm by a friend, and Hsieh, who jumped from a window to perform Jump Piece (1973), breaking both of his ankles. To this day, Hsieh prefers not to discuss this work. However, these actions represent the antithesis of efficiency, having more in common with self-mutilation associated with deserters during active service, and workers trying to get off the production line through self-inflicted injury, which are essentially extreme forms of a ‘go-slow’.

However, for “Are You Working Now?”, it is Hsieh’s One Year Performance, which is most suitable as an icon of challenging our notions of time, labour and value, in contrast to a Taylorist efficiency. Introducing Teching Hsieh in Sheffield, UK, in the early 1990s, the artist replied, “thanks Mike, for wasting my time”, a provocation potentially insulting the host and the audience, but really provoking a question as to the value of time spent at its most fundamental level.

In One Year Performance: Time Clock Piece (1980–81), Hsieh ‘clocks-on’ every hour for a year, day and night. Here, Hsieh rejects our assumptions on how we spend our time, begging fundamental questions on how we create value and how we value time spent. Not only that, but he also challenges fundamentally any notion of ‘productivity’ as might have been determined through an efficiency study, as prescribed by Taylorism, or the invention of the process of mass production in Henry Ford’s car plant in the early 1920s. In the classic film, Modern Times (1936), Charlie Chaplin still reminds us how we are always trying to keep up with the machine; here, he is quite literally being crushed by a cog. Then, in a new modernist world, the fear of industrialisation seemed real and clear, with anxieties of time, space and productivity made manifest.

Rosie Gibbens work riffs off Modern Times, in which she takes the pressures of female identity, and self-improvement into a gym-like space a stage further, and with no shortage of irony. Titles such as Planned Obsolescence and The New Me reflects a culture in which we are soaked by endless feeds of how we all need to better ourselves, to be healthier, to perform more efficiently and to comply with stereotypes and norms.

Artists have explored most aspects of the contemporary world, suggesting new modalities of life and existence. New types of relationships and scenarios, formed through digital networks, artificial intelligence and big data, present incredible opportunities and challenges. In adjusting to a society where productivity continues to increase, while employment opportunities decline, we are becoming detached progressively from the physical mechanical world our forefathers helped to shape. Our current pervasive socially-networked condition is a happy bundle of work-life balance, 24/7. We are the machine. Systems of value creation, labour and self are further entwined. As we wrestle with new realities of a globalised experience economy, the boundaries between work and recreation have become increasingly blurred. We are confronted with learning new definitions of consumption and production, with our multiple digital identities across shrinking distances in compressed time. The abstraction of our digital domain is diminished constantly, as our ability and desire to see finer detail and track everything algorithmically advances. As our devices to perceive this detail improve, so we can better define the way digital becomes tangible. Time is money. Data is money.

Data always has been material, and even in 1995 from Nicholas Negroponte’s Being Digital1 we learned that the cables along which this data travelled were the new motorways. We have no excuse to consider digital as an abstraction, nor drone attacks, nor cyber bullying. Operators flying unmanned drones into battle fields do know when they kill the enemy. Legal systems and ethics lag behind breakthroughs in AI, as we recognise its labour-saving ability and its impact on society, perhaps sharing similar patterns with the invention of the steam engine and mechanical looms. Surveillance capitalism captures our current condition, one we unwittingly help to construct, where the benefits and ease of doing things seamlessly in digital environments appear to outweigh the risks of data theft and totalitarianism. Morphogenesis of Values by Maurice Benayoun, takes the most prescient aspects of the commodification of data, value and emotion, extending the ideas of Mark Fisher captured in the publication Capitalist Realism: is there no alternative? Despite all the warnings and self-knowledge, we still believe in the future as technologies come up with solutions. Our greater awareness of the finite nature of fossil fuels and the damage caused in mining the same, drives a need search for alternative minerals to reach renewable and cleaner energy sources. An increased need for rare-earth metals, cobalt or lithium, comes with similar issues. How do we cut emissions from mining, as we still need the steel, and the concrete needed to do the mining, and making the machines? Demand for dysprosium and neodymium could quadruple between now and 2050, and while we may have the reserves, how do we extract these resources e will generate more emissions while we build new energy sources, and the machines and buildings in which to do the mining, but such emissions will be less than if we continue to burn fossil fuels.

Artist Inari Wishiki refers to this as ‘unmaking’, and this aligns with an increasing interest in ‘degrowth’.2 Design for Disassembly, is an example, of an artwork asks another way to look at built-in obsolescence and life cycles of objects, getting us to think beyond the sale of the object as the end point in an economy not designed for sustainability. With combined technologies and learning, we can rethink manufacture and disposal, considering the end of the life of products, the conversion of waste to fuel, whether this is digital noise, redundant data, bio-mass, or the clinker from smelting iron, and this is what Ned Rossiter terms ‘dirt research’.3 Of course, this leads to using less, and expecting less.

Since the Industrial Revolution, we have built the ability to produce and consume more, but this sense of infinite growth, fathomless seas and endless space is gone. Scarcities in resources and options are intertwined tightly, to the point where, once again, we look to the stars. Geologists estimate that to achieve global Net Zero, there will have to be more mining in the next few decades than there has been throughout history. Here on earth, humans are approaching the physical limits of growth. Scarce natural resources trigger rivalry among states, drawing them into wars, and here, scarcity of options is at work, to avert disaster. Furthermore, apart from AI being seen as our saviour, it will also consume vast amounts of energy, which will need even more resource mining to produce that energy. This is set against the backdrop of knowing that, on Earth, we have a finite amount of energy, simply because the Earth is a limited size collector of its energies, only exposed to part of the sun’s radiation, so if there is no such thing as infinite energy, can there be exponential growth?

Factory of the Sun, by Hito Steyerl, takes us to the sun and back. Are we in real life, or is it a game? Light is both the medium and the subject. Factory of the Sun tells the surreal story of workers whose forced moves in a motion capture studio are turned into artificial sunshine.

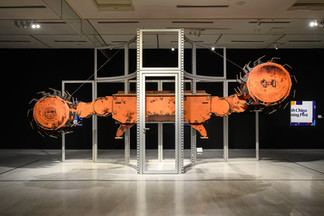

Mine, by Simon Denny, invokes an uncanny sense of materiality and ephemerality, researching the interrelationships of technology, networks and power. In making heavy industrial machinery out of more ephemeral materials, this is playing between the physical and the digital.

John Gerrard’s Western Flag is a generative work which both speaks poetically to waste, fossil fuels and territory, and is built on layered research into the specific site of the world’s first major oil find, which was in Spindletop, Texas in 1901. The site is now barren and exhausted. Meanwhile, Pithole in Pennsylvania, where the first commercial oil well was drilled in 1865, had become a ghost town by the 1880s, so it is evident that the fossil fuel industry has always been on a roller-coaster ride. Over a one-year period, Gerrard built a complete model of the site in CGI, creating a 3D simulacra of the geography and industrial architecture. This work acknowledges the history of the place, and at the same time it demonstrates the value of virtuality, which is in common with games engines which create detailed ‘real’ metaverses.

Recent figures indicate that more than 228 million people play Minecraft, a game where, beginning with a landscape and a pickaxe, players can produce or ‘mine’ their own virtual world. It is a mass phenomenon that has captured imaginations and instincts, in an environment of online collaboration, industry and destruction. Dubbed ‘first-person Lego’, this is a sociable space of design, asset management, life and death, and a game with few rules, placing the player at the centre of a domain to be built. Games like this are the manifestation of media theory, and of experiments practised by scientists and media artists in the past, now providing user-friendly bricks in the redefining of our understanding of identity and embodiment. With novel values of exchange proliferating across all aspects of life, trading digital assets is imbued with as much belief as collecting art or mining for gold. For a 10-year-old, putting the pick down is difficult, albeit in a virtual environment. How can we self-educate as a species to find function and purpose without work?

The Coming Insurrection, a French political manifesto, describes contemporary working life thus:

Today work is tied less to the economic necessity of producing goods than to the political necessity of producing producers and consumers, and of preserving by any means necessary the order of work. Producing oneself is becoming the dominant occupation of a society where production no longer has an object: like a carpenter who’s been evicted from his shop and in desperation sets about hammering and sawing himself.4

Striving to achieve a work/life balance and, for some, being enabled to work anywhere, at any time, how are we going to differentiate along these traditional divisions? Nineties’ fantasies of working from the beach may have materialised for the super-rich. Alternatively, doing nothing and letting machines do all the work (if you own them) is now a real possibility; meanwhile, there are real people in factories in Taiwan manufacturing microchips that make this possible. This is at the core of Taiwan’s industrial strategy (providing most of the high-end chips, globally), and it is a source of labour for many needing work. Even more complex are the geo-politics that come with stewarding possibly the world’s most significant commodity or knowledge base, and the recombination of rare earth metals/ knowledge and labour.

The rubric of eight hours ‘work, eight hours’ leisure and eight hours’ rest – fought hard for in the nineteenth century during the campaign for the eight-hour day – evaporates for most of us as our leisure is the work and our work the leisure. One’s presence in social media on multiple platforms is just another job (instagram: @mike_stubbs). How are those underemployed contributing within new economies across the world, as consumers and players, or is this just a means of dressing-up mass unemployment, and of shifting the problem as employment patterns change? The export of labour is a smart way of making things seem clean and seamless, especially if mining and manufacturing take place on ‘foreign’ lands.

As manufacturing represents only one in ten jobs in the USA, and is increasingly automated with industrial robots, this begins to show a trend whereby productivity continues to grow while employment diminishes. Whatever dirty labour remains to be done can be migrated to the latest place where people work for the lowest wage, where robots are too expensive or have not, as yet, had designed-in those competencies. However, this is a transitionary phase – as healthcare and education become distributed via new technology, and mining becomes automated, we really could be heading for a worldwide state of unemployment. How do we want that to look and to feel?

My grandfather owned his first watch on his retirement, when he needed it least. Until then, he had relied on the Vickers shipyard hooter to signal the end of the working day, as did his wife, as the signal to prepare his dinner. The hooter was the town’s clock. Work has been the primary focus for social engagement, and for giving many people a sense of purpose in the world. What happens when we take that away? Mass mental illness or a renaissance of philosophy and global understanding? Workers leaving a factory are more difficult to discern when they are remote workers logging out of their computers, in isolation, but although the factory gates may be digital, they are just as real for most. In the Lumière film of 1895, Workers Leaving the Factory Gates, there is clearly a factory and a place of work, and, of course, it was the first film shown publicly depicting workers leaving the photographic products factory in Lyon.

Workers Leaving the Factory Gates, also features in Workers Leaving the Factory, by Harun Farocki, along with a sequence from Modern Times. Working on multiple levels, this documentary essay addresses: piece work, surplus value, Marxism, gender politics, heavy industry. Many of these themes are also explored by the works in “Are You Working Now”. Importantly, taking the factory gates as a site of conflict, shows that the Lumière film already carries within itself the germ of a foreseeable social development: namely, the disappearance of this form of industrial labour, as we move to a future world of work made of hybrids of networks, databases and machine learning.

The utility of time spent is less easy to evidence when work has become tacit in a knowledge economy, or through transactional work, such as in the service industries, than it is in what Jeremy Myerson terms ‘transformational work’, where objects are hewn of stuff and raw materials, such as steel, are converted into cars.

Value creation relies on the suspension of disbelief, meaning that the act of persuasion and transaction has always had as much to do with commanding a good salary over earning a wage through brute strength and stamina, often based on historic distortions of power and privilege. The knowledge economy is testament to that. Within the context of looking in an art gallery, audience behaviours and learning are as important to our economy of operation and function as the production of the art itself. We count visitors attending a free exhibition to prove the social worth of the art experience, or we sell tickets and the market dictates its need. To reveal the tacit understanding within the transactions, and to understand better where lies the intrinsic quality in a contemporary centre, where we have already pioneered consumers becoming producers with digital technology, we use both algorithms and personal contact with more effect.

Understanding digital preferences and ‘liking’, driven by powerful algorithms, real-time feedback loops can improve products, services and our overall experience. The symbiosis between tourist guide and tourist, seller and shopper, artist and audience, are constantly monitored to improve business. Taken across most aspects of society, all our relationships and experiences could become more refined, efficient and pleasurable, leading to an improved quality of life for all. But how is automation, with its new rhythm of time and space, helping to spread the load when, for many, work continues to look like it did for their grandparents: physical graft? How will we spend our time in the future when we are still wedded to expectations, models of labour and societal contracts located in the 19th Industrial Revolution.

Within this context, “Are You Working Now” at NTMoFA is an experiment in collaborating with a range of creative producers and researchers across the venue, and with audiences, with work and with digital spaces. It is a creative enquiry into new types of working life, asking the public to contribute their views, and also to contribute to a real-time experience, provoking and challenging us to question how we spend our time, and whether we are working or playing. As we move from utopian fantasies of labour-saving devices to a reality of ‘endless work’, mass surveillance and cyber-loafing, how are we coming to terms with these new patterns and social impacts?

We are living in the paradox of a society of workers without work, where entertainment, consumption and leisure only underscore the void from which they are supposed to distract us. The mine in Carmaux, France, famous for a century of violent strikes, has now been reconverted into Cap’Découverte, an entertainment multiplex for skateboarding and biking, distinguished by a Mining Museum in which methane blasts are simulated for holidaymakers. Coal mining or sugar cane production provide a fraction of the opportunities they did in the past, and they are also a reminder of prior colonial interests.

This is not only a polemic on work and labour and a questioning of fairness, but is also a proposition on how we can ‘extract’ value and meaning through observing the incidental and the incremental; how we can accept that quality can be found in most things, and how we can genuinely innovate better means of extending across space and time. We need more equitable forms of exchange, to re-engineer our notions of acquiring something for nothing, and the need to ‘extract’ as a given. The relationships between value creation, wealth and a terminal condition for the Earth are inter-related, and the term extractionism is currently useful in re-thinking the relationships materials, beings and consciousness, and fairer transactions. Our perception of living, animal and all elements of the ecology become finer with increased science to measure and shifting understanding of sentience and what finite.

“Are You Working Now” asks questions, which allow us collectively to dwell on social equity and collective consciousness, provoking a new set of goals which are less reliant on digging up grit... to turn into gold.

Read full programme:

1. N. Negroponte, Being Digital (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1995).

2. In the context of De-growth artist Inari Wishiki has initiated an (Un)-maker Faire, a practical provocation in how we make and can consume less. Website (Accessed 19 June 2023).

3. N. Rossiter, ‘Dirt Research’, Depletion Design: A Glossary of Network Ecologies (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2012).

4. The Invisible Committee, L’insurrection Qui Vient (The Coming Insurrection) (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2008: 32).

Comments